Saturday 18 July 2015 - 13:11

Story Code : 172432

Scuttling Iran deal might not be easy for next president

But it may not be that easy.

If Iran lives up to its obligations, a new president could face big obstacles in turning that campaign promise into U.S. policy. Among them: resistance from longtime American allies, an unraveling of the carefully crafted international sanctions, and damage to U.S. standing with the rest of the world, according to foreign policy experts.

"The president does not have infinite ability to get other countries to go along with them," said Jon Alterman, director of the Middle East program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. "One of the consequences is the United States would be increasingly isolated at a time when Iran is increasingly integrated with the rest of the world."

Both Obama and Republicans know firsthand the difficulties of dismantling major policies, a task that only gets harder the longer a policy has been in place.

After more than six years in office, Obama has failed to achieve his promise to shutter the Guantanamo Bay prison, despite signing an executive order authorizing its closure on his first day in office. And more than five years after Obama's health care overhaul became law, Republicans have been unable to find a legal or legislative means for repealing the sweeping measure.

While some elements of the nuclear accord don't go into effect immediately, the centerpiece of the agreement is expected to be implemented quickly. If Iran curbs its nuclear program as promised, it will receive billions of dollars in relief from international sanctions.

To Republican presidential candidates, rolling back that quid pro quo would be a top priority if they were to win the White House.

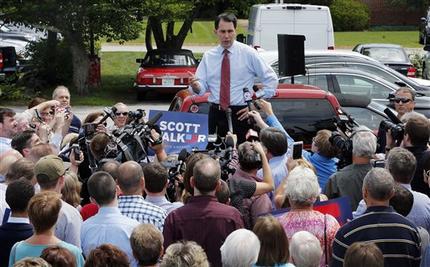

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker says he would "terminate the bad deal with Iran on day one" and work to persuade allies to reinstate economic sanctions lifted under the deal. Former Texas Gov. Rick Perry concurred, saying one of his first actions in office would be to "invalidate the president's Iran agreement."

Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor, said that while he would consult with allies about the deal on his first day in office, he was inclined to "move toward the abrogation of it." Florida Sen. Marco Rubio told The Associated Press he would withdraw from a deal even if allies objected.

The next president has no legal obligation to implement the nuclear agreement, which is a political document, not a binding treaty.

But if there's no sign Iran is cheating, it's unlikely the European allies, who spent nearly two years negotiating alongside the U.S., would be compelled to walk away and reinstate sanctions. And it's nearly impossible to imagine Russia and China, which partnered with the U.S, Britain, France and Germany in the talks, following a GOP president's lead.

"Shattering something like this with the British and the French and the Germans - that has consequences," said Ilan Goldenberg, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security and former Obama State Department official. "A new president isn't going to want to lead off like that."

To be sure, a U.S. president with a friendly Congress could unilaterally reinstate American sanctions on Iran. But the economic impact would be far less if other countries didn't follow Washington's lead.

Beyond Europe's interests, the White House says U.S. partners in Asia, including Japan and South Korea, will also likely have boosted their financial ties and oil purchases with Iran by the time a new president takes office in January 2017.

A wealthier, more globally integrated Iran is a scary prospect to opponents of the deal. Republicans contend Obama signed off on a weak deal with Iran, leaving the Islamic republic on the brink of building a bomb. Some say the president should have left the negotiating table, increased economic pressure on Iran, then resumed talks with greater leverage.

The president says the only realistic alternative to the diplomatic agreement is war.

Congress has 60 days to review the Iran deal. While lawmakers can't block the agreement itself, they can try to pass new sanctions on Iran or block the president from waiving existing penalties.

Some Republicans say the White House is trying to pre-empt congressional actions by seeking an endorsement of the nuclear deal at the United Nations Security Council next week. Tennessee Sen. Bob Corker, the chairman of the Senate foreign relations committee, wrote Obama a letter urging him to postpone the U.N. vote until after Congress considers the agreement.

The White House says the U.N. vote has no bearing on the status of unilateral American sanctions on Iran.

But Michael Hayden, who served as CIA director under former President George W. Bush, says the White House's push for quick U.N. action seems to have a longer-term goal than circumventing this Congress. Seeking the United Nations' stamp of approval for the deal, Hayden said, appears to be "for the express purpose of locking in the next president of the United States."

By The Associated Press

# Tags