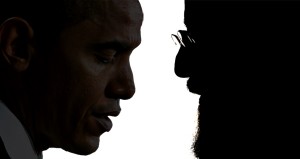

While American officials say the near miss between�President Obama�and President Hassan Rouhani of Iran at the United Nations General Assembly on Tuesday means little to the ultimate fate of negotiations with Iran over its�nuclear program, it does illustrate the acute political sensitivities that will affect both leaders as they try to embark on a diplomatic path.

While American officials say the near miss between�President Obama�and President Hassan Rouhani of Iran at the United Nations General Assembly on Tuesday means little to the ultimate fate of negotiations with Iran over its�nuclear program, it does illustrate the acute political sensitivities that will affect both leaders as they try to embark on a diplomatic path.After two days of discussions between American and Iranian officials about a potential meeting of the leaders, a senior administration official said the Iranian delegation indicated that it would be �too complicated� for Mr. Rouhani and Mr. Obama to bump into each other.

�We did not intend to have a formal bilateral meeting and negotiation of any kind,� said a senior administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the negotiations. �For them, it was just too difficult for them to move forward with that type of encounter at the presidential level, at this juncture.�

For its part, the White House did nothing to dispel speculation about a meeting. It might well have felt confident, given that Mr. Rouhani was granting interviews to American broadcasters, in which he struck a remarkably moderate tone. On Tuesday morning, the�General Assembly�was buzzing with rumors of a history-making encounter. Hopes flagged when Mr. Rouhani failed to show up for a lunch given by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, which would have provided the best venue for a handshake.

By the time Mr. Rouhani took the rostrum at the United Nations late on Tuesday afternoon, however, it was clear that he felt compelled to undertake a slight course correction. In a speech that seemed pitched as much to a domestic audience as to a room of world leaders, he unfurled a familiar list of grievances, speaking of the repression of the�Palestinian�people and �warmongering� forces in the United States.

Mr. Rouhani�s words were a far cry�from the inflammatory rhetoric of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. He did not mention Israel, let alone wipe it out. Nor did he deny the existence of the Holocaust. But his message was clearly aimed at placating hard-line elements in�Iran, who analysts say will be quick to undermine Mr. Rouhani�s attempt at diplomacy if he is perceived as moving too fast.

A handshake with the president of the United States � on the heels of Mr. Rouhani�s other conciliatory gestures � might well have been interpreted that way, American officials said. �Every leader has his or her own politics,� the senior official said. �That�s certainly the case with President Rouhani.�

In his speech, the official noted, Mr. Obama repeated his vow never to allow Iran to acquire a nuclear weapon. He also said Americans viewed Iran as a country that declared the United States an enemy, and has killed and injured Americans, either directly or through proxies.

There was a sense of history repeating itself at the United Nations. In September 2000, President Bill Clinton asked his aides to try to engineer an impromptu encounter with Iran�s then-President Mohammad Khatami � like Mr. Rouhani, a moderate. After much discussion about logistics, Mr. Khatami declined the offer.

A former senior adviser to Mr. Clinton, Bruce O. Riedel, said the Americans concluded that Mr. Khatami was not willing to take the political risk that would have come from a meeting with the president. Mr. Khatami�s political position in Iran was arguably weaker than Mr. Rouhani�s today.

White House officials said they were not worried that Mr. Rouhani might deliver a less than conciliatory speech after greeting Mr. Obama. His indirect criticisms of the United States and Israel, they said, were no surprise, and in any event, they said, Mr. Obama did not view meeting the heads of even adversarial countries as a concession.

�The very fact that they were unwilling to go forward with it demonstrates that they were the ones who had discomfort with it in terms of dealing with their own complexities back home,� the senior official said.

By The New York Times

The Iran Project is not responsible for the content of quoted articles.