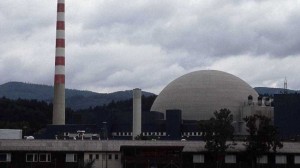

A view of Iran�s Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant[/caption]

A view of Iran�s Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant[/caption]In the latest issue of�The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, seasoned Iranian ambassador Hossein Mousavian has once again�highlighted�the possibility of an Iranian withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Mousavian maps out the various scenarios facing incoming Iranian president Hassan Rouhani in dealing with the decade-long negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 over the country�s nuclear program.

Mousavian explains that in the event a compromise between both sides cannot be found, Iran will most likely exit the NPT. Iran�s logic for doing so would be two fold.

First, it would be based on the conviction that the United States and her partners have no intention of ever removing the mounting sanctions regime on the country.

Second, it would be grounded in the belief that being bound to the treaty allows the United States and other pliant actors to use alleged Iranian violations of the NPT to facilitate and enhance those sanctions, which have gradually erode the Iranian economy and by extension the state.

Although this reasoning has been previously been analyzed by many�analysts, including myself, and some Iranian�politicians, it has never been so forcefully and systemically explained by a senior, albeit former, Iranian official like Mousavian.

As a result, Mousavian�s article has elicited a series of mixed responses. Some have described his claims as an Iranian bluff. Others have viewed his proposed scenario as a reactionary move that will invariably escalate tensions between Iran and the P5+1. Still others have reacted by professing sincere confusion regarding Iranian intentions.

Many still doubt whether Iran will ever move toward withdrawal from the NPT, misunderstanding the utility of such an action.

Most commonly, analysts believe Iran would never withdraw from the treaty because it would elicit violent backlash from the West, particularly from the United States. Any potential benefits Iran might gain from the move would be subsumed by the additional onslaught of sanctions that would surely come its way. As Peter Jenkins has�argued, this time around, such a supposedly reactionary Iranian move may provoke the support from Russia and China towards the US position.

Thus, according to this line of thinking, Iran is �stuck� with the NPT and the only way for sanctions relief is through negotiations, which may occur either through a compromise between both sides or total capitulation by Iran.

Even under these circumstances, the notion of �sanctions relief� may ultimately have vastly different meanings for either side, making it possible that additional sanctions may be forced upon Iran for issues which may or may not be related to its nuclear program.

Though in his piece Mousavian describes the logic of Iran�s withdrawal from the NPT�vis-�-vis�Iran�s past negotiations with the P5+1, in an�article�I wrote last year for�The National Interest, I described how Iran would initiate such a step, and more significantly, what the benefit of this move would be � predicated, of course, upon the insolubility of the nuclear standoff.

Indeed, it is these two points � the�way�in which Iran withdraws from the NPT and the benefits to Iran in a post-withdrawal environment � that have received the least attention. To properly address these points, it is important to also broaden the discussion to wider aspects of international law and understand how other actors in the international system have responded to the extraterritorial nature of the US sanctions regime.

A Rational Reaction

As I stated last year, an Iranian withdrawal from the NPT would not represent some ill-begotten temper tantrum, an ad hoc reaction to mounting pressure, or a frenzied attempt at sanctions relief.

It would be neither an optimal nor painless option. Rather, it would be a decision Iran would be forced to make given the sanctions� destructive effects and the prospect of endless negotiations with parties that, from Iran�s perspective, have little incentive to compromise.

For Iran, what would ultimately bring about war is not leaving the NPT in the short term, but rather staying with the treaty indefinitely

The sanctions currently being piled on Iran are not designed to facilitate a diplomatic resolution or elicit �a change in Iran�s nuclear policies or its approach to negotiations,��primarily because,�as written, they require fundamental changes to the governing structure of the Islamic Republic (i.e.�regime change).

It is true that a determined, politically able president can override much of the sanctions language and somewhat sideline the US Congress, which has designed these measures. It has, however, traditionally been Congress, not the president, that has won these struggles, particularly as it relates to Iran.

Again, it is possible if the Obama administration secures a dual compromise with the Rouhani administration, it could bypass Congress, sell the deal to the American people, and force legislators to accept a negotiated settlement with Iran as a�fait accompli.

But those are all big �ifs�, and while perhaps not impossible, they are hard to imagine.

As it currently stands, the sanctions regime is � by design or default � slated to sufficiently degrade Iranian military and economic might to create better conditions for military intervention.

For these reasons, an Iranian exit from the NPT would be like stepping out of the way of an oncoming train.

The move would surely be complex and systematic. It would involve a give-and-take process in which Iran decouples itself from a problematic legal quagmire created by the NPT. As Mousavian explains, �since the 1979 Revolution�[the NPT] has proven more harmful than beneficial for Iran,� serving merely as �a national security threat, whereby the West has used it as an instrument to bring Iran to the United Nations Security Council.�

Iran�s Right to Withdraw

Iran�s willingness to withdraw from the NPT is increased by Rouhani�s landslide win in the country�s June 2013 presidential elections, his�newly-established reformist-centrist coalition, and the public mandate he currently enjoys, as evidenced by massive voter turnout (over 70%).

In the event that Iranian decision-makers decide to opt out of the NPT, they will invoke�Article X.1, which states:

Each Party shall in exercising its national sovereignty�have the right to withdraw�from the Treaty�if it decides that extraordinary events, related to the subject matter of this Treaty,�have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country. It shall give notice of such withdrawal to all other Parties to the Treaty and to the United Nations Security Council�three months in advance. Such notice shall include a�statement of the extraordinary events it regards as having jeopardized its supreme interests. (emphasis added)

The Iranian leadership would trigger this clause with full knowledge that Iran�s departure from the NPT would dramatically exacerbate an escalating conflict with the United States and Israel.

But, since Iran is already enduring massive economic warfare from the West, it would be far more advantageous for Tehran to change the terms of the conflict sooner rather than later.

As I�wrote�last year, once Iran has submitted its notice of intention to exit the treaty to the Security Council,

Tehran likely would point to the years of cooperation with the IAEA as having failed to allay the agency�s concerns. It can point to the escalating sanctions, cyber attacks, assassinations and the fact that the benefits of NPT membership have been chipped away. And despite there being no concrete evidence of the existence of a nuclear-weapons program, Iran would highlight how U.S. accusations of Iran�s NPT violations have brought about draconian sanctions that impact the country�s economic standings and the quality of life for its citizens. Hence, the Iranians could claim that continuing membership is only facilitating economic warfare against it and that these �extraordinary events� have �jeopardized its supreme interests,� forcing it to leave the treaty.

It is also conceivable that Iran would give the Security Council an ultimatum, stipulating that its continued membership hinges on the complete normalization of its nuclear file in the IAEA.

When this ultimatum is inevitably rejected, the Iranians will use this as proof both of their willingness to diplomatically resolve the issue and their opponents� recalcitrance.

Under this scenario, Iran�s desired outcome would be to dampen the international outcry concerning its withdrawal and possibly generate solidarity from non-aligned countries.

So, would Iran�s decision to leave the NPT mean war?

In the three-month period before Iran�s formal withdrawal from the NPT is complete, the likelihood of an attack may very well increase.

At the same time, if Iran remains a party to the treaty, an eventual attack by the United States (or possibly Israel with American support) may in fact be inevitable, once sanctions have sufficiently degraded the Iranian state.

A War of Words

While an Iranian exit from the NPT would certainly exacerbate diplomatic tensions, reactions from the United States and allied countries are likely to predominantly be rhetorical, provided the move is tactfully implemented.

However, there is no concrete evidence the United States will, in the foreseeable future, use military action against Iran to prevent the�possibility�it may manufacture nuclear weapons � something the country is already technically capable of doing.

While the Obama administration, like its predecessor, has verbally committed itself to the possible use of force, the conditions for war with Iran are simply non-existent.

Breakdowns in the prevailing political and security make-up of the Middle East caused by such a war would virtually guarantee that its negative ramifications � including a crippling of the global oil market and the world economy � would last for years, possibly engendering an incurable multigenerational rupture in the international system.

Crucially, there is no political will in the United States for another war. The United States and other OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries do not have the economic capacity to either prevent or withstand the catastrophic ramifications of another regional war. The unambiguous aversion to conflict with Iran among the American military leadership has also seldom been as pronounced as it is now.

Most importantly, war does not jibe with the patterns of US interventions over the last fifty to sixty years.

Although clearly enjoying military superiority over almost all other state actors, the United States has not gone to war with strong centralized countries that have the military capacity to resist or defend against invasion. Any objective view of how and when the United States engages in conflict clearly demonstrates it intervenes in states that have already failed or are in the process of failing or disintegrating (i.e. Vietnam, Yugoslavia, Haiti, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, etc.).

The Future of Sanctions

This leads to the question of how sanctions would affect Iran post-withdrawal. Will a NPT exit bring sanctions relief or would it enhance and further aggravate the regime?

Traditionally, two avenues have been used to wage economic warfare against Iran: the UN Security Council (UNSC) and US-led sanctions that are both unilateral and extraterritorial.

For a number of reasons, it is unlikely the UNSC will once again act against Iran.

The last time the Security Council was unified over Iran sanctions was in 2010, after the United States rejected the Tehran Declaration, an initiative signed by Iran, Brazil, and Turkey to revive the October 2009�confidence building measure�between Iran and the IAEA/United States/France/Russia. Under this agreement, Iran would have sent out more than half of its stockpile of low enriched uranium in exchange for fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor.

In order to push through the 2010 sanctions resolution, the United States had to partially �buy off� the Russians by agreeing to abandon plans to station missile defense systems in Eastern Europe. As for the Chinese, their voting pattern in the UNSC has typically been aligned with Moscow.

Today, things are drastically different.

The United States has little to offer Russia and China to win their support for more sanctions. More importantly, the relationship between both countries and the United States has deteriorated quite substantially � relations with Russia have been particularly rocky thanks to NATO�s intervention in Libya in 2011, the on-going Syrian civil war, and the broader ramifications of the Arab Spring.

The Russian and Chinese�veto�of Security Council resolutions imposing sanctions on Syria foretells a similar reaction to any renewed efforts to build consensus on Iran.

Even the curious case of NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden is telling. The Russian government could easily hand him over to the United States, but has decided against it. Currying favor with Washington just is not a priority anymore.

If Russia and China are unwilling to act at the behest of the United States when it comes to Snowden or Syria, the likelihood they will agree to measures that will increase conflict with Iran remains low.

Indeed, one can argue that recent escalations in US sanctions against Iran, in tandem with its EU and Persian Gulf allies, is a direct result of Washington�s lack of options at the Security Council.

Eroding Consensus

The most profound, open secret surrounding the Iranian nuclear program has been eroding consensus in the P5+1, so much so that the Putin administration openly�stated�last year that the US sanctions regime against Iran is intended for regime change. The implications of this statement are huge, as it goes to the core of US credibility in using sanctions against Iran.

If the Russians and Chinese perceive the US sanctions regime as intended to create conditions for war, there is a high probability, predicated upon Iranian diplomatic finesse, that they would acquiesce to Iran�s exit from the NPT.

They have nothing to lose in doing so, and could blame the diplomatic failure on the United States and EU for refusing to engage in reciprocal compromise with Iran.

American Extraterritoriality

But what about third-party states that have been pressured by the United States into abiding with US sanctions.

The latest (and most painful) barrage of sanctions levied against Iran by the United States and the EU, and the massive pressure by the US government to persuade other countries to comply with its diktats, is primarily based on the claim that Iran is violating its �international obligations� by allegedly violating the NPT.

Though critics of the US sanctions regime consistently imply that the nuclear issue is simply a ruse to apply pressure on Iran � either in the hopes of bringing about Iranian capitulation or some fantastical notion of regime change, it is Iran�s continued and active membership in the NPT that has allowed the sanctions regime to expand.

The key term � �international obligations� � hovers over the background of virtually every�US statement concerning Iran, including Congressional sanctions resolutions, White House statements, and even perfunctory Nowruz greetings from the president. It also pervades much of the language about Iran used by American allies and countries vulnerable to US pressure.

For example, the recently instituted EU boycott against Iran is not because of Iranian support for Hezbollah. Similarly, the fact that South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan have agreed (thanks to US pressure) to limit oil trade and economic and financial dealings with Iran is not because of the latter�s regional policies. Rather, these and other countries are acting in response to the claim that Iran is in violation of its �international obligations� � regardless of its veracity.

In light of this reality, Iranian membership in the NPT has become the primary reason for the sanctions. Iran has significant incentive, therefore, to leave the NPT and �free� itself of its �international obligations� � particularly if it believes the nuclear issues is being used as a pretext for inevitable military aggression.

Worldwide Impact

Though unable to force Iran�s capitulation or economic collapse, it is self-evident that sanctions clearly hurt both the Iranian government and its people.

Few understand, however, that these sanctions also damage other governments and their people.

In truth, the detrimental effects of the sanctions are felt globally. For instance, last year, due to increasing sanctions,�the�French auto industry, which at one time had robust economic ties with Iran, laid off approximately 11,000 autoworkers because of revenue lost from withdrawing from the Iranian market.

Many German industries have watched their profit margins suffer as once strong economic ties with Iran have massively deteriorated due to US pressure. As a result, China and, to a lesser extent, Russia and India have picked up where Europe left off.

Southern European countries, such as Greece and Italy, which traditionally have heavily relied upon Iranian oil imports, have also had a difficult time with the limitations imposed on their economies.

With Iran no longer beholden to the NPT, some of these states will begin to question participating in the sanctions regime and restricting their own economies.

Their reasoning will be quite simple. Because Iran is no longer treaty-bound, it is not in �violation� of any �international obligations� as it relates to its nuclear program.

Once this taboo is broken, it is only a matter of time before many countries restart their very lucrative trade deals with Iran.

This will all be compounded by domestic developments within EU countries. EU firms tied to the Iranian market have openly pushed for their governments to withdraw from the sanctions regime to protect their profit margins from further loss � a reality�recently�highlighted by EU courts that have challenged the trade and financial restrictions European governments have placed on Iran.

Conclusion

The US government�s ability to force other states to tighten sanctions on Iran has and will continue to weaken. Should Iran decide to leave the NPT, US influence over other countries will deteriorate even further.

While political problems cannot be solved solely through technical formulas, there are ample reasons why Iran may be inclined to withdraw from the NPT.

A negotiated settlement involving equal concessions by both sides, as well as reciprocal implementation that addresses the political and technical aspects of the deal, would be the best scenario for all concerned parties.

At the same time, given perceptions in Iran that the US-led West is neither ready nor willing to agree to such a deal, Iran�s continued membership in the NPT, a regime that facilitates onerous sanctions on the country, would be a self-defeating and dangerous exercise.

By Muftah

The Iran Project is not responsible for the content of quoted articles.