Iran hawks in Washington don’t want a nuclear agreement; they want Tehran to surrender its sovereignty and national rights.

Iran hawks in Washington don’t want a nuclear agreement; they want Tehran to surrender its sovereignty and national rights.

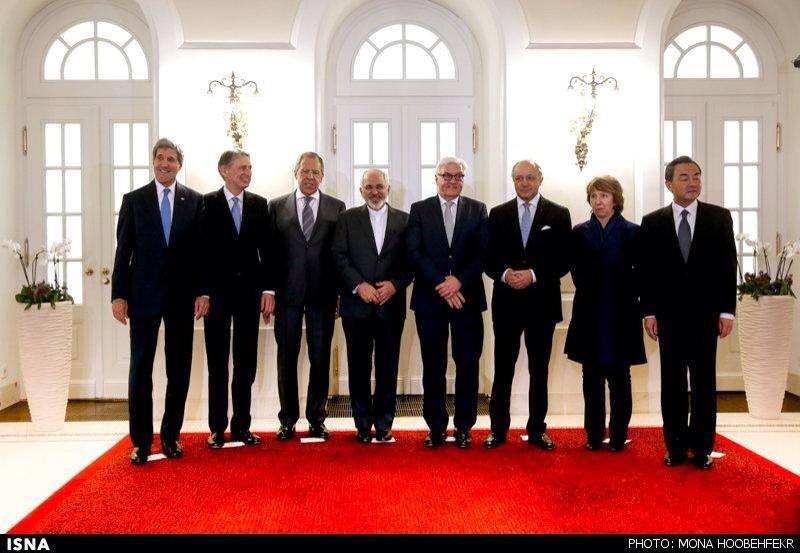

As the prospects of a comprehensive nuclear agreement between Iran and the P5+1—the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany—brightens, Washington’s hawks seem to have gone into panic mode. They do not seem to want any agreement unless Iran says “uncle,” gives up its sovereignty and national rights within the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and completely dismantles its nuclear infrastructure. They’re asking Iran to capitulate, not to negotiate. That’s an unrealistic goal—and in their dogged pursuit of it, they have overlooked serious steps Tehran’s taken that demonstrate a desire for compromise.

We see this unfortunate dynamic in an article this month by Mark Dubowitz, Executive Director of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, published in the National Interest. Dubowitz’s main premise is that it was the economic sanctions imposed by the United States and its allies that brought Iran to the negotiation table, and only more economic sanctions will induce it to surrender. The premise is false. While the sanctions did play a role, they were not the most important reason, or even one of the primary ones. Iran is negotiating because that is what it has wanted—contrary to Dubowitz’s assertion that “Iran does not appear to be ready to compromise.”

President Hassan Rouhani, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, and their diplomatic team have always been interested in a compromise. Between February 2003 and August 2005, Rouhani was Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator under former president Mohammad Khatami. Zarif was the senior diplomat taking part in the negotiations between Iran and three European Union powers, Britain, France and Germany (the EU3). At that time, Iran proposed to limit the number of its centrifuges to three thousand, put Iran’s nuclear program under strict inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and impose other limitations. In return, Iran asked only for security guarantees by the United States and the EU3. The proposal was rejected by the George W. Bush administration and the EU3.

Earlier, in May 2003, the Khatami administration had proposed a comprehensive plan for addressing all the major issues between Iran and the U.S., including strict limits on Iran’s nuclear program. But, that proposal too was rejected by the Bush-Cheney team that was still drunk on “mission accomplished” nonsense, and less than a year prior had been crowing that “real men go to Tehran.” The opportunity slipped away.

Since Rouhani and his team have long been interested in a compromise, it’s no surprise that they’re seeking one again. But the facts on the ground have changed since 2003. So have Iran’s conditions for a compromise. Whereas Iran did not have a single centrifuge operating in 2003-2005, it now has nearly ten thousand centrifuges spinning and producing low-enriched uranium, with another ten thousand centrifuges waiting to be started. The Rouhani administration will not go back to its 2003 proposal. In fact, even if President Rouhani did want the same deal, Tehran’s hardliners would immediately impeach him. But Iran has stated repeatedly that it could live with an agreement whereby Iran’s current operating centrifuges will continue to work, but no new centrifuges will be installed for the duration of the agreement. Iran’s desire for a deal is genuine.

Dubowitz also suggests that the U.S. has made all sorts of concessions to Iran, that even “the goalposts [of a final deal] appear to be moving,” while Iran has held fast. This is completely false. In fact, Iran has made five major concessions.

One is agreeing to limit the number of its centrifuges for the duration of the comprehensive agreement. By doing so, Iran has temporarily given up its rights under the NPT—that treaty imposes no limit on the number of centrifuges that a member state can have, so long as they are under IAEA inspections and for peaceful purposes.

The second concession is about Iran’s uranium enrichment facility built under a mountain in Fordow, near the holy city of Qom. It was a thorny issue for a long time. The United States had demanded that Iran dismantle the facility altogether. The facility is, however, suited neither for military purposes nor large-scale industrial use. It was built by Iran to preserve its indigenous enrichment technology in case the larger Natanz enrichment facility was destroyed by bombing—a threat that multiple states have made. Abbas Araghchi, Iran’s deputy foreign minister and a principal nuclear negotiator,has emphasized repeatedly and emphatically, “Iran would not agree to close any of its nuclear facilities.” Iran has agreed to convert the site to a nuclear research facility, representing a major concession.

This article was written by Muhammad Sahimi for National Interest on DEC. 24, 2014. Muhammad Sahimi is Professor of Chemical Engineering & Materials Science and the NIOC Chair at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. For nearly two decades he has been analyzing Iran's political developments and its nuclear program.

The Iran Project is not responsible for the content of quoted articles.

QR code

QR code