Robert A. Levinson was an overweight bear of a man who once worked as an F.B.I. agent and desperately wanted to recapture the life of international intrigue he relished as an expert on Russian organized crime. But as he sat in a hotel room in Geneva in early 2007, he was anxious about a secret mission he had planned to Iran.

Robert A. Levinson was an overweight bear of a man who once worked as an F.B.I. agent and desperately wanted to recapture the life of international intrigue he relished as an expert on Russian organized crime. But as he sat in a hotel room in Geneva in early 2007, he was anxious about a secret mission he had planned to Iran.

“I guess as I approach my fifty-ninth birthday on the 10th of March, and after having done quite a few other crazy things in my life,” he wrote in an email to a friend, “I am questioning just why, at this point, with seven kids and a great wife, why would I put myself in such jeopardy.”

He would like some assurance, he added, that “I’m not going to wind up someplace where I really don’t want to be at this stage of my life.”

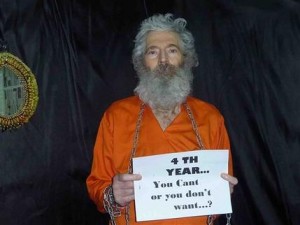

Mr. Levinson gambled and traveled to an island off the Iranian coast to meet with an American fugitive he hoped to turn into his informant. There, his worst fears were realized — he disappeared, and has since been seen only as a prisoner in a video that emerged about three years ago and in photographs showing him dressed like a Guantánamo detainee, in orange garb.

Since his disappearance in March 2007, United States officials have publicly insisted that Mr. Levinson went to Iran as a private investigator working a cigarette smuggling case. In fact he was also a contractor for the C.I.A. As the real purpose of his mission became known within the government, it led to a scandal within the C.I.A. in which three agency officials lost their jobs, for, in effect, using Mr. Levinson as part of an unauthorized spying operation.

The New York Times has known about the former agent’s C.I.A. ties since late 2007, when a lawyer for the family gave a reporter access to Mr. Levinson’s files and emails. The Times withheld that information to avoid jeopardizing his safety or the efforts to free him. On Thursday, The Associated Press disclosed Mr. Levinson’s role with the intelligence agency. In a statement, the White House said it had urged the wire service not to publish its article “out of concern for Mr. Levinson’s life.” After Thursday’s disclosure, the Levinson family said it had no objection to The Times’s publishing this article.

The Iranian government has maintained that it knows nothing about Mr. Levinson’s fate. High-ranking American officials have long said privately that they believe the Iranians view him as a spy and that he was being held by a group tied to Iranian religious leaders, possibly the Revolutionary Guards.

In many ways, the story that emerges from Mr. Levinson’s files and dozens of interviews is that of an unusual spy, an aging but still passionate investigator searching for a way to keep his hand in the game. It is also the story of officials in a relatively obscure C.I.A. office looking to push the boundaries between the agency’s analytical side and its covert operations. An agency inquiry concluded that those analysts had encouraged him to take risks and then misrepresented his activities after he went missing.

To his family and friends, the government Mr. Levinson served for decades abandoned him for a time, initially making little attempt to find him or acknowledge why he went to Iran.

They started their own search, and a cast of unlikely figures was drawn into the hunt, many seeing it as an opportunity to get something for themselves. They included an infamous weapons dealer, Sarkis Soghanalian, and one of Russia’s most powerful businessmen, Oleg Deripaska.

In late 2010, when his family received the tape of Mr. Levinson, they saw a man they barely recognized. He was gaunt. His shirt was threadbare. He was seated in a makeshift prison cell.

“I need the help of the United States government to answer the requests of the group that has held me,” he said, as music played in the background. “Please help me get home. Thirty-three years of service to the United States deserves something.”

A Career Revived by ‘Toots’

Mr. Levinson might have stayed at the F.B.I. for his entire career, but he retired in 1998 because he needed money. He and his wife, Christine, had seven children, and there were college bills to pay.

While at the F.B.I., he became a specialist in Russian organized crime figures and had a knack for developing informants. Mr. Levinson was gregarious by nature, the “good cop” who liked everybody and wanted everyone to like him. But he also had a tendency to ignore his supervisors if he believed in a case, a trait that got him into trouble at times. “Bobby thought that everything he was getting was gold,” said one former F.B.I. official. “Sometimes it was, and sometimes it wasn’t.”

After retiring, Levinson worked for several large investigative firms and then ran his own business from his home in Coral Springs, Fla. But he badly wanted a way back into government, and a C.I.A. analyst named Anne Jablonski helped him out.

The two shared a specialty in Russian organized crime and were close friends. In emails, he called her “Toots” and signed off as “Buck.”

In 2006, Ms. Jablonski worked for a C.I.A. unit called the Illicit Finance Group that produced reports on subjects like money laundering and international corruption. In the years after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, the C.I.A. expanded greatly, hiring hundreds of outside contractors.

Mr. Levinson was thrilled when Ms. Jablonski told him in mid-2006 that he had been approved for a consulting contract.

“Today is my thirty-second wedding anniversary and aside from celebrating those years with Christine, I’m going to (prematurely) celebrate this,” he wrote. “It seems like something too good to be true. I really look forward to working with you and trying to make a contribution. Yeah, you really made my day, Toots.”

He was told the finance group was interested in information about several countries, particularly Iran and Venezuela. In the case of Iran, C.I.A. analysts wanted to know how it might respond to trade sanctions and also wanted potentially embarrassing information about Iranian officials, the investigator’s notes show.

In the nine months before his disappearance, Mr. Levinson unleashed a flood of more than 100 memos that together read like a disjointed catalog of chaos, crime and intrigue from countries throughout Central and South America and Eastern Europe — mostly countries he was visiting as a private investigator.

After Mr. Levinson disappeared, some C.I.A. officials questioned the value of his reports. But in 2006, Ms. Jablonski and her colleagues believed he was scoring points for them in the competition between the two sides of the agency, the analytical and the clandestine branches. Only the clandestine branch is supposed to operate covertly, but since the C.I.A. had not established rules after the Sept. 11 attacks governing the operation of contractors, Mr. Levinson had a freer rein, and his bosses at the agency were eager to let him roam.

“You’d have SO enjoyed being a fly on the wall today in our meeting about you,” Ms. Jablonski wrote Mr. Levinson in mid-2006. “Everyone was so happy about the info but just freaking out about how to NOT piss off our ops colleagues for doing a better job than they do. Seriously — we have to tread carefully here.”

The Iran Connection

Mr. Levinson knew his way around some parts of the world, but he knew nothing about the one country that his bosses at Langley were most interested in: Iran.

The path that took him there began with another friend, Ira Silverman, a retired NBC investigative producer. Mr. Levinson had been one of the newsman’s sources for law enforcement tips, but now Mr. Silverman had a tip for the investigator. He could connect him with someone who might prove to be a source in Iran, Dawud Salahuddin, an American who had fled there in 1980 after assassinating a former aide to the shah of Iran in Bethesda, Md.

Mr. Silverman had met Mr. Salahuddin in 2002 when he went to Tehran to profile him for The New Yorker. The fugitive viewed many Iranian officials as corrupt, and Mr. Silverman believed he might be willing to share information. He particularly disdained a former Iranian president, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, privately claiming he had stolen millions in oil revenues and secretly invested it in Canadian real estate and other assets. Mr. Silverman introduced the two men by phone.

Mr. Levinson wrote to Mr. Silverman that he thought the relationship had potential and said that “what I hoped was that I became more than just another voice on the telephone.”

Mr. Levinson went to Toronto to try to track Mr. Rafsanjani’s money. While there, he also met with a Lithuanian-born businessman, Boris J. Birshtein, who in time would lead him to some Iranians. But the world Mr. Levinson was wading into was getting trickier. Mr. Birshtein, a short, stocky man in his 60s, was believed by the authorities to have hosted a meeting in the 1980s of top Russian organized crime figures. While Mr. Birshtein denied any criminal ties, American authorities kept his name on a border list, making it difficult for him to enter the United States.

In exchange for information, Mr. Levinson offered to try to fix his problems at the border, writing: “Let ME try to get this straightened out once and for all.”

Soon afterward, Mr. Birshtein arranged for Mr. Levinson to attend a meeting at an Istanbul hotel with two Iranians who were on their own mission. They were looking to buy critical materials for Iran in the event that Western embargoes were tightened and offered to supply discounted oil in return.

Mr. Levinson detailed the meeting in a December 2006 report to the C.I.A., calling it a “real biggie.” But about that same time, he had exhausted the funds available under his initial C.I.A. contract. Ms. Jablonski suggested he take a break until more money became available.

“Oh, Bobby, everyone’s MORE than satisfied — they are thrilled,” she wrote. “But right now the problem is the coffers are EMPTY and so there’s just nothing to pay for the extra at this point. But trust me, everyone is THRILLED.”

Even so, Mr. Levinson continued filing reports. In February 2007, he sent an email that would later loom large over the question of what the C.I.A. knew about his Iran trip. It was sent to Ms. Jablonski with the subject line, “Urgent Note for Mr. Tim,” a reference to the head of the Illicit Finance Group, Timothy Sampson.

Mr. Levinson wrote that he was going to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, to work on several non-C.I.A. cases, including one involving cigarette smuggling, and hoped to meet someone there “or on an island nearby” who claimed to know about money laundering by Iranian officials.

Meanwhile, Mr. Silverman was helping to arrange Mr. Levinson’s meeting with Mr. Salahuddin at the Maryam Hotel on the island of Kish, a short flight from Dubai.

“Our guy just called. Very relaxed,” Mr. Silverman wrote in one email. “He foresees no problem for himself or for you. Says he’ll be in the lobby, early morning wearing a black beret.”

“Love that touch with the beret,” Mr. Levinson replied. “Sounds like something out of ‘Casablanca.’ ”

On March 8, 2007, the investigator packed a small bag with toiletries, a change of clothes and gifts he had purchased. He did not check out of the hotel room in Dubai, expecting to return the following day.

“Off today for that place — all is set — best wishes and thanks for all your help in getting this arranged,” he wrote to Mr. Silverman.

“Bob, so good to have your words,” his friend responded. “Please get back to me when you can.”

By the next day, Mr. Silverman had not heard anything, so before going to bed, he sent an email.

“Bob. How are you doing?”

When Mr. Silverman awoke, he checked his computer. There was no response. It was March 10, Mr. Levinson’s 59th birthday.

An Official Apology

As Mr. Silverman frantically worked the phones over the next few days searching for his friend, he got several explanations from Mr. Salahuddin. The fugitive first told the former newsman that he had been taken away for questioning by the Iranian police, who had made a surprise visit to the Maryam Hotel. When he returned the next morning, he was told that Mr. Levinson had just departed for the airport, Mr. Salahuddin told Mr. Silverman.

A few days later, Mr. Salahuddin said the authorities had taken Mr. Levinson to Tehran for questioning. “He was saying: ‘Everyone has got to be quiet. It can get resolved early,’ ” Mr. Silverman recalled.

Mr. Silverman worried that he had misjudged Mr. Salahuddin. He also had never imagined that his friend might have gone to Iran without the approval of the C.I.A. or a backup plan to get out.

To Mr. Levinson’s family and friends, it slowly became clear that neither the F.B.I. nor the C.I.A. considered finding him a priority. The C.I.A. officials also had plenty of reasons to hide their connection to Mr. Levinson, both from the public and from others in the agency.

When word of Mr. Levinson’s disappearance filtered back to the C.I.A. days later, Ms. Jablonski heard the news and went to a bathroom and threw up. Years later, she told a reporter that she had immediately alerted her superiors that Mr. Levinson might have gone to Kish on the C.I.A.'s behalf, although the internal investigation questioned her account.

The F.B.I. also initially did little. While bureau technicians retrieved the hard drive from Mr. Levinson’s computer in his Florida home, its contents were apparently not examined for more than a year, associates said. Offers of help from Mr. Levinson’s colleagues were also rebuffed or ignored by F.B.I. officials.

“They were freezing people out,” said Jeffrey Katz, the head of a London investigative agency that had worked with Mr. Levinson.

David McGee, a former federal prosecutor and a lawyer representing the Levinson family, said of the F.B.I.: “You knew when they did not care about a case, and they did not care about this one.”

In March 2008, a year after Mr. Levinson’s disappearance, his wife was called to a meeting at F.B.I. headquarters. There C.I.A. officials acknowledged for the first time that he had worked for them. Had it been left up to the C.I.A., it is unlikely that meeting would have occurred.

Mr. McGee and Mr. Silverman had given records from Mr. Levinson’s files that documented his C.I.A. work to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. Senator Bill Nelson, Democrat of Florida, called in top agency officials and demanded an explanation. Those officials said they had never been alerted that an agency contractor was missing and promised to investigate.

Not long afterward, two C.I.A. officials met with Ms. Levinson and Mr. McGee at his office in Pensacola, Fla. They started by delivering a message. “They wanted to officially apologize on behalf of the C.I.A. to the Levinson family,” Mr. McGee recalled.

According to Mr. McGee, the C.I.A. officials said that while an inquiry had not found a “smoking gun” proving that the agency knew in advance about Mr. Levinson’s trip, it did conclude that Ms. Jablonski and her boss, Mr. Sampson, had misled officials about his work.

The agency gave Ms. Jablonski, Mr. Sampson and another top C.I.A. analytical official a choice: They could resign from the agency or be fired, according to several people familiar with the matter. Mr. Sampson and the other official resigned. Ms. Jablonski said she had refused and was fired. In 2008, when Mr. McGee made it clear he was prepared to sue the C.I.A., the agency agreed to pay $2.25 million to Ms. Levinson, whether or not her husband returned.

Ms. Jablonski, who now works for a financial consulting firm, said in an interview that the C.I.A.'s suggestion that she had abandoned a friend to protect her career was a lie. She said she had never imagined Mr. Levinson would go to Kish and insisted that she would have stopped him had she known.

She described herself as a convenient scapegoat for the C.I.A. She said that during the agency’s internal inquiry she had been repeatedly interrogated inside a windowless room by two former operatives. The men belittled Mr. Levinson’s intelligence reports as useless and suggested she might have been complicit in his disappearance.

“For all we know, you were angry with your friend and sent him to Iran to be killed,” she said one of them told her.

An Unusual Search Party

Whether Mr. Levinson is still alive is a mystery. But his family and friends, and eventually, the United States government, have spent years trying to find him.

Initially, Mr. McGee, Mr. Silverman and a retired F.B.I. agent, Larry Sweeney, mounted their own search. They were put in touch with a former weapons dealer named Sarkis Soghanalian, known in his prime as “the Merchant of Death.”

Mr. Soghanalian, a heavyset man with a neat mustache, had once lived lavishly in Paris and Beirut, Lebanon. But by 2007, he was 78, in financial trouble and infirm. He lived in a house behind the Miami airport and was largely confined to a single room equipped with a bed, a wheelchair, a small table and a telephone. He used a crude rope-lift that hung above his bed to pull himself up.

He offered to tap his network of Middle East contacts, but he, like others, viewed the search as an opportunity for personal gain.

Mr. Soghanalian, who wanted to get back into the weapons trade, claimed people he knew could help negotiate Mr. Levinson’s release and said government approval for some weapons deals would speed the process. He fed the family hopeful stories of sightings of the former agent in refugee camps controlled by Hezbollah, and once he announced that Mr. Levinson’s release was imminent.

“It’s all in the oven,” he said.

At Mr. Soghanalian’s behest, Mr. McGee and Mr. Silverman flew to Cyprus to meet a supposed intermediary with Hezbollah. The men arrived with a security team, prepared to bring their friend home. But after several days of talks, it was clear the intermediary knew nothing.

Ms. Levinson feared that her husband’s captors were intensely interrogating him or worse. He was also overweight and had high blood pressure.

Near the end of 2007, she walked into the Maryam Hotel on Kish and was greeted by a headline in an English-language Iranian newspaper that read, “Wife of Missing American in Iran.” At age 57, she was on her first trip outside the United States, retracing her husband’s footsteps in a vain attempt to find clues.

Ms. Levinson, her son and her sister handed out fliers at the Kish airport that showed her husband holding his grandson. They returned to Tehran where they met in a hotel tearoom with Mr. Salahuddin.

He struck his visitors as anxious, quickly shifting topics and stuttering at times. He gave Ms. Levinson a gift her husband had given him, a copy of “The Black Dahlia,” James Ellroy’s account of a Hollywood starlet’s unsolved murder.

Mr. Salahuddin told them he had been foolish to think two Americans could meet safely on Kish and said he believed Mr. Levinson was being treated well.

“He told me how much he liked my father,” Mr. Levinson’s son Daniel said. “He said he thought he might be sitting in a hotel room somewhere learning Farsi.”

By mid-2008, the F.B.I. was fully engaged in the hunt. At that time, two F.B.I. agents met at a Paris hotel with a powerful new player who became secretly involved in the effort: Oleg Deripaska, one of Russia’s wealthiest businessmen.

Mr. Deripaska’s entry into the case held great promise. He headed an international mining and metals empire with business ties to Iran.

His involvement also came with a price. The State Department had refused Mr. Deripaska a visa because of allegations linking him to organized crime — accusations he has denied. But Mr. Birshtein, the Toronto businessman, had approached the F.B.I. with a plan: He would persuade Mr. Deripaska to join the search and, if they succeeded, both would get their entry problems resolved.

Mr. Deripaska said he would put up millions to fund the venture, but he insisted that his role be kept secret. However, word that big money was in play made its way to Iran. Suddenly, a man with family connections to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, insisted that he could engineer Mr. Levinson’s release for a hefty price. F.B.I. officials were so confident about the plan that they told Mrs. Levinson to stay by the phone for a call from her husband. It never came.

Mr. Deripaska, who was scheduled to meet in 2009 with bankers in the United States, wanted to collect on his end of the deal. The State Department, after two heated meetings with Justice Department officials, refused to issue him a visa, according to government officials. The F.B.I., hoping to keep him in the game, made an end-run around State Department officials and issued him a visa under a special program, allowing him to enter the country twice.

In 2010, during a visit to New York, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, then the president of Iran, was asked about Mr. Levinson by reporters. He said his government knew nothing of the former agent’s fate but offered to help find him.

A few months later, in November 2010, an email with the video of Mr. Levinson attached was sent to Mr. Silverman and others. It was followed a few months later by another email with the picture showing him dressed as a prisoner. Around the same time, top F.B.I. officials met with their Iranian counterparts for secret talks about Mr. Levinson. But they quickly fizzled.

Iranian negotiators kept saying that a radical splinter group had kidnapped Mr. Levinson and that they were carrying out raids to find him. F.B.I. officials feared the story was a setup to allow the Iranians to take Mr. Levinson to a remote place and kill him as part of a “raid” to set him free.

For Mr. Levinson’s family and American officials, the more moderate posture of Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, raised the prospect that the Levinson episode might come to a close, one way or another. His name has been raised by President Obama in talks with Mr. Rouhani, but again he said Iran knew nothing about Mr. Levinson and offered to help.

On Thursday afternoon the family received an email from an Associated Press reporter telling them the news organization planned to release an article within a few hours that would disclose Mr. Levinson’s ties to the C.I.A., a secret the family had held closely.

Later that day, the family issued a statement calling for the American government to “take care of one of its own,” saying that “after nearly seven years, our family should not be struggling to get through each day without this wonderful, caring man that we love so much.”

By The New York Times

The Iran Project is not responsible for the content of quoted articles

QR code

QR code